There are Wolves in England

In a village quaint, by the sleepy town’s embrace,

Lived a huntsman, skilled, with a weathered face,

with tales and fortunes, he wished to sow.

He dreamed of lions roaming wild and free,

In a mirror, his wishes aged like leaves on a tree

as the winds of fortune for he, worked slow.

Jim and Jay, the Huntsman’s sons, so contrary,

Learned manners well from Aunt Mary.

and Uncle Wells, who raised them bright,

Jim and Jay, two lads of curious delight,

With winds at their backs, they’d set their sights,

On tales told by one who left. They too planned flight.

Adventures contrary to cousin Selena’s plan,

contrary to conduct learned from a wise old man.

In this sleepy town, where life was slow,

not far off, prowling like a wolf, a terrible robber man,

who roamed the woods, with his dark, wicked plan.

Such adventures only Nicholas Henry would know.

“There are no wolves in England now,” they said,

As they tucked their children into cozy beds,

By the cat, the milk jug sat forgotten in the glen,

Nicholas Henry, outside windows, listening to stories told,

to Jim and Jay Henry of his love, felt less bold.

As four paws prowled; the gardener’s cat again?

Poor Henry, once a lad with a twinkle in his eye,

Sought treasures ‘neath the moonlit sky.

Tongues whispered secrets in hushed delight,

With four paws, the gardener’s cat roamed far and wide,

Guarding against the terrible robber man’s stride.

As Jim and Jay ventured out into the night.

“There are no wolves in England now,” they’d say,

But still, they feared the night and its shadowy display.

Years ago, Nicholas Henry sat by the fire’s glow,

In the coop, the hens clucked and laid their eggs,

While the rabbit nibbled near the milk jug’s edge,

Nicholas Henry spoke of journeys far and dreams to follow.

Poor Nicholas Henry, he sighed beneath the moon’s glow,

As tongues whispered secrets only he’d know,

“There are no wolves in England now,” they’d say,

As Jim and Jay ventured where fairies danced,

In the moonlight’s shimmer, their joy enhanced.

But still, they feared the night and its shadowy display.

Fairies danced in the moonlight’s gentle beam,

Their silvery gowns a wondrous, magical gleam.

as the huntsman who had returned as a robber,

as the Fairies sang their lullaby sweet,

guiding sleepy boys to the wolves to meet,

as Poor Henry decided to be a father,

The dance of adventure, a lullaby so sweet,

By a crackling fire in a rocking chair’s seat,

Poor Henry, slumber beckoned with a gentle nod,

In a rocking chair, by the hearth’s warm ember,

When he lost his sons, he lost tales to fondly remember.

Now only in dreams does he see them abroad.

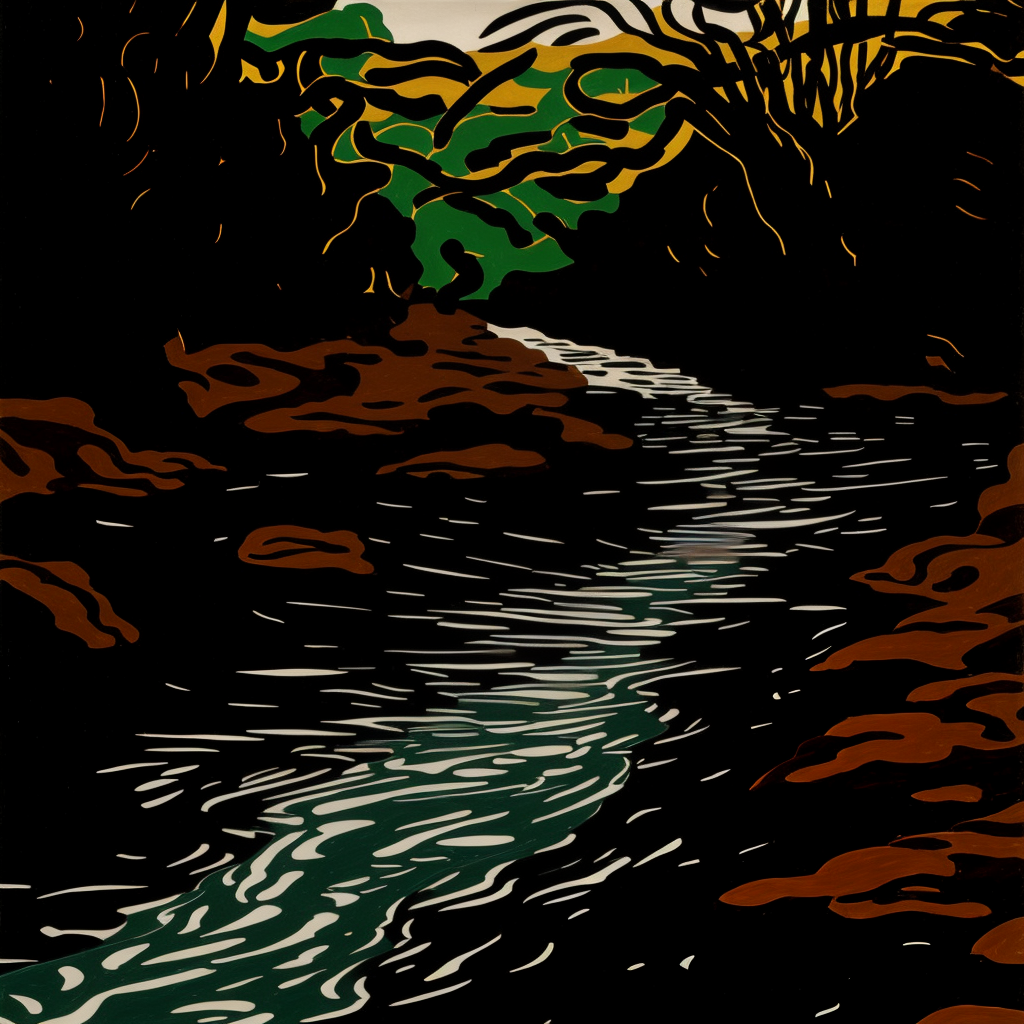

Sarah B. Royal’s There Are Wolves in England, composed through her signature Table of Contents constraint, is a rich, folkloric narrative that blends pastoral nostalgia with mythic unease. Drawing from the titles of a 1925 poetry anthology, Royal constructs a world where bedtime stories blur with lived experience, and the line between man and beast is as thin as moonlight on a glen. The poem is a masterclass in tonal layering—at once whimsical, elegiac, and quietly chilling.

At its surface, the poem reads like a storybook tale: a quaint village, a weathered huntsman, two curious boys, and a lurking threat in the woods. But beneath this familiar structure lies a deeper meditation on generational longing and the mythic residue of English folklore. The refrain—“There are no wolves in England now,”—functions as both reassurance and denial. It echoes like a charm spoken to children at bedtime, a cultural incantation meant to soothe. And yet, the poem insists, wolves still prowl—not in fur, perhaps, but in the form of “a terrible robber man,” in the shadows of regret, and in the wildness that civilization pretends to have tamed.

The poem’s central figure, Nicholas Henry, is a tragic archetype: once a dreamer, now a father haunted, His sons, Jim and Jay, are spirited and imaginative, drawn to adventure and the unknown. Their upbringing—“manners well from Aunt Mary,” “conduct learned from a wise old man”—is steeped in tradition, yet their hearts yearn for something beyond the sleepy town’s embrace. Their story becomes a parable of youthful rebellion. The wolves they were told didn’t exist become real—not just as external threats, but as metaphors for the dangers of ignoring instinct.

Royal’s use of the Table of Contents constraint is particularly effective here. The poem’s language is steeped in the diction of early 20th-century verse—“wayfaring souls,” “moonlight’s shimmer,” “tongues whispered secrets”—which lends the narrative a timeless, almost enchanted quality. These borrowed titles are decorative as well as structural, forming the bones of a story that feels antiquitated. The constraint becomes a kind of literary séance, summoning the ghosts of forgotten poems to tell a new tale.

The recurring imagery of animals—the cat, the rabbit, the hens, and of course, the wolves—grounds the poem in a natural world that is domestic and untamed. The gardener’s cat, with its “four paws prowling,” becomes a guardian figure, a silent sentinel against the encroaching dark. Meanwhile, the fairies who “dance in the moonlight’s gentle beam” offer a counterpoint to the wolves: they are the magic that protects, the lullaby that soothes, even as they guide the boys toward their fate.

The poem’s final stanzas are deeply poignant. Nicholas Henry, now old and alone, sits by the fire, remembering the sons he lost—not just physically, but to the wildness he once chased. “When he lost his sons, he lost tales to fondly remember.” This line encapsulates the poem’s emotional core: the idea that stories are not just entertainment, but inheritance. When we lose those we love, we lose the stories they would have told, the adventures they would have lived. The wolves in England, then, are not just predators—they are the embodiments of time lost and stories unlived.

In There Are Wolves in England, Royal has crafted a poem that is both a fairy tale and a cautionary tale, a lullaby and a lament. Through her constraint-based method, she breathes new life into forgotten titles, weaving them into a narrative. It is a poem about the stories we tell to keep the dark at bay—and the truths that slip through anyway, like wolves through the hedgerow.

Leave a comment